To think of Uruguay means to think about meat. The livestock industry has been the main economic activity in the country since the beginning of its history. The country’s economic boom starting in the twentieth century marks the peak of this industry, when dozens of meat salteries and cold storage facilities packed the landscape of the Uruguay River coast. Nowadays, the remains of these salteries and cold storage warehouses have become traces of an industrial heritage of great value directly associated with the river. These ruins have been hardly acknowledged.

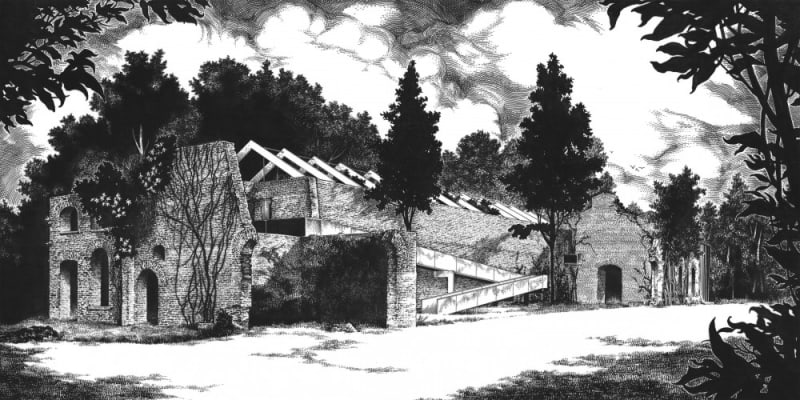

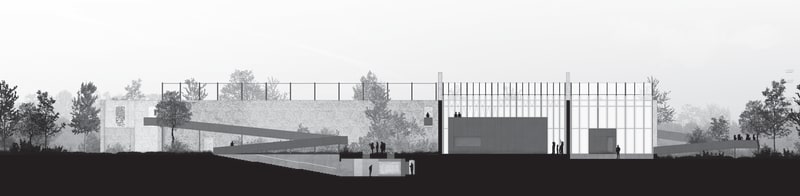

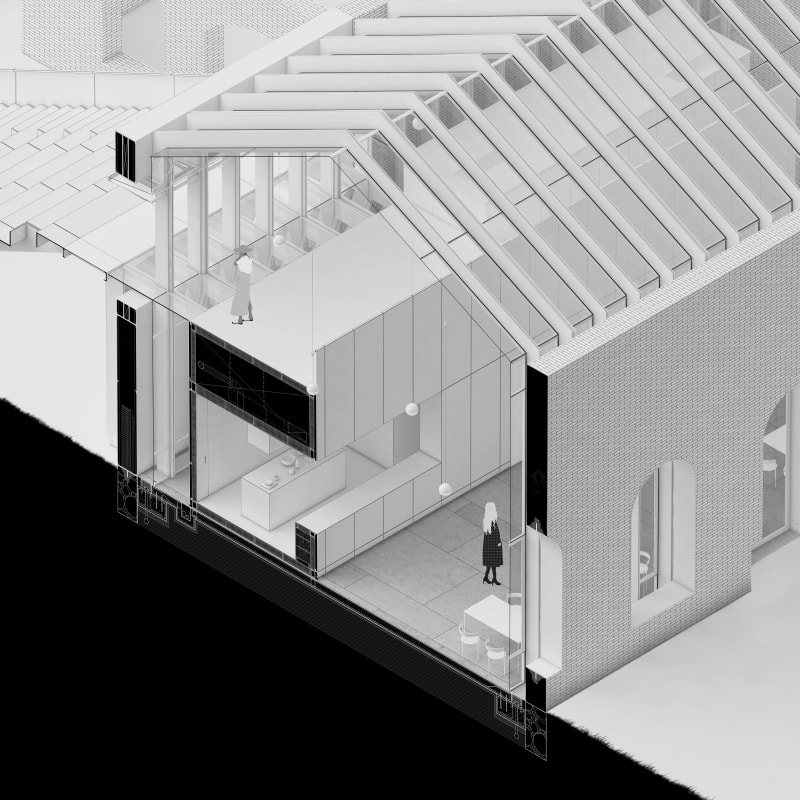

The proposed project understands heritage as thought of by Alberti and Palladio, all the way through to the present, pursuing an alternative focus that reflects the contemporary mindset. M’bopicuá is a cold storage facility founded by English at the end of the 1800s, which today grants the project a set of particular starting conditions such as the constructive system, its state of ruin, the ingrown vegetation within the building, the native forest that surrounds it. Considering all these factors, it is conceived as an intervention that generates another level of comprehension, a parallel reality.

The Piranesian conception of the ruin, the romanticism reflected in the Vedute di Roma prints is what it is projected on. The phenomenological is taken as a premise and spaces are walked through in search of an amplified experience, one that enhances the virtues of the saltery. Continuity between intervention and preexistence is given as a compromise of opposites. The inclusion of new elements will establish connections with that which was already part of the location, found morphologies that in spite of the differences between materials and technologies share shapes and are linked by working together as a whole. The contrast between the new and the old is continuously pursued, thus emphasizing the passing of time. The ruin will remain a ruin and the intervention will inevitably become one.

From the beginning we decided to address the issue of architectural heritage in our country, since nowadays it is going through a sort of crisis, where a great deal of works have been lost due to negligence. Making an intervention on this situation would mean to face the many limitations of this context and being able to get through them.

For that end, it was necessary to find patterns throughout the Uruguayan territory that allowed the possibility of an intervention made not only on a particular level, but also on a series of elements with common characteristics.

The field of study we chose was the coastline of the Uruguay river, where dozens of salteries and meatpacking plants were built during the nineteenth century, colonizing the landscape and impulsing the meat industry as the main economic activity of our country. However, due to different reasons as the new technologies or even state policies, their activity decays and they eventually shut down.

Nowadays, their remains leave marks of an industrial heritage that has great value linked to the river, although they present an important damage and are far from the recognition they should get.

As a way of trial we took the particular case of Saladero M’Bopicuá, a declared National Monument dating from 1875 located in the Rio Negro province, that ended activities after only 3 years of functioning.

The abandoned building was soon invaded by the native forest recovering the place that it once owned, covering it almost completely. This way the historical and patrimonial value of the remains was complemented with the landscaping values of its presence.

Firstly, we aimed to build the theory that would justify our actions and gave us tools to work with, basing ourselves on concepts about heritage, from Palladio to Alberti, including Camilo Boito and all the way to the contemporary days.

We looked for the contrast between the new and the old over and over, more like a conciliation between contraries than a denial from one another.

Another tool that we explored was the time factor. If the ruins are the end of architecture, we would be here building a ruin over a ruin, two tales that coexist. As the “parlante ruini” that Piranesi described in his series of prints called Vedute di Roma, they communicate and they move, making the visitor a main character.

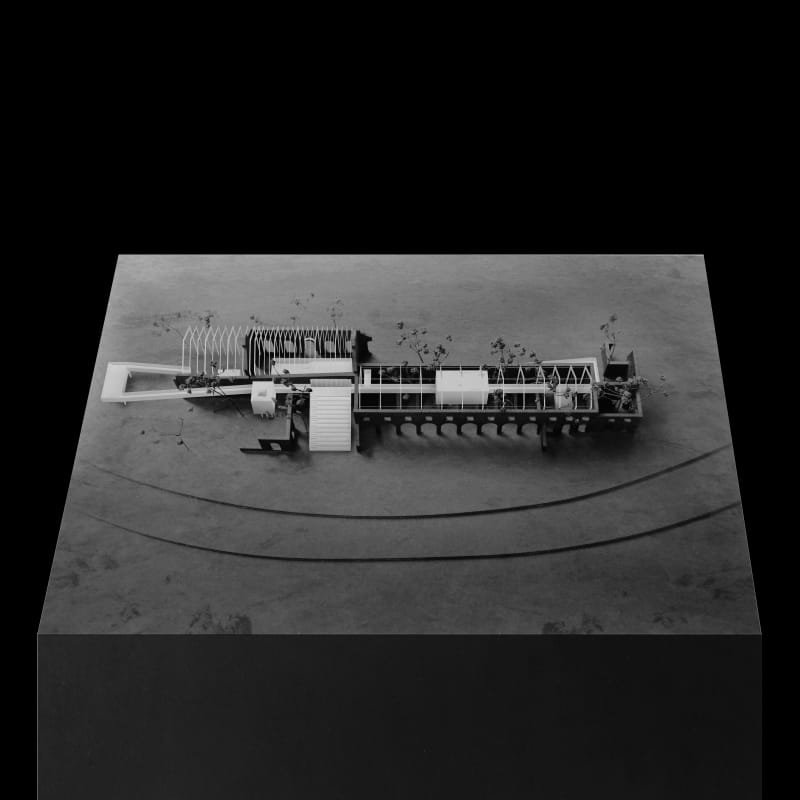

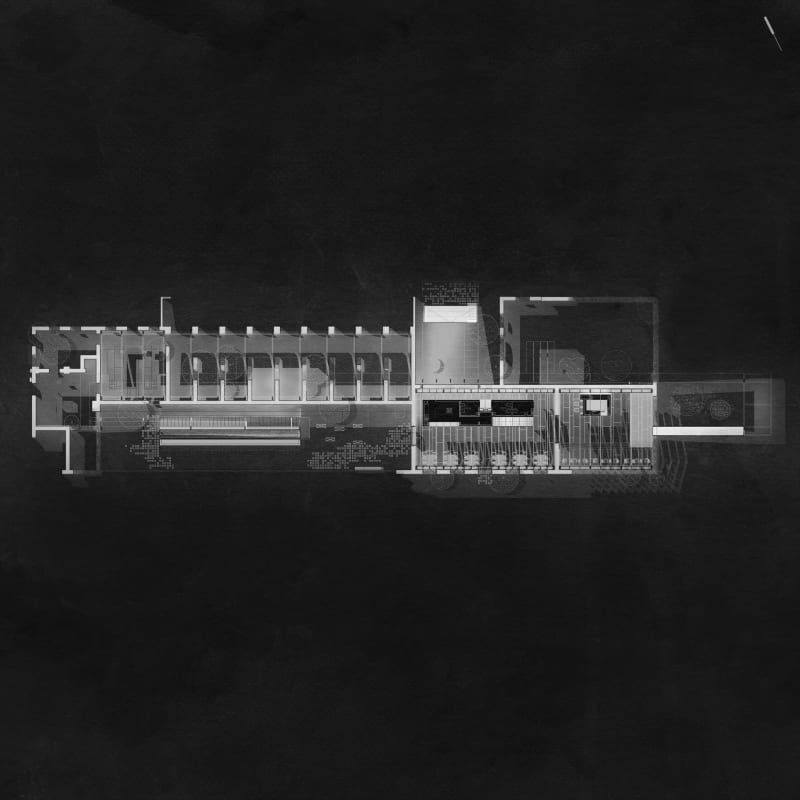

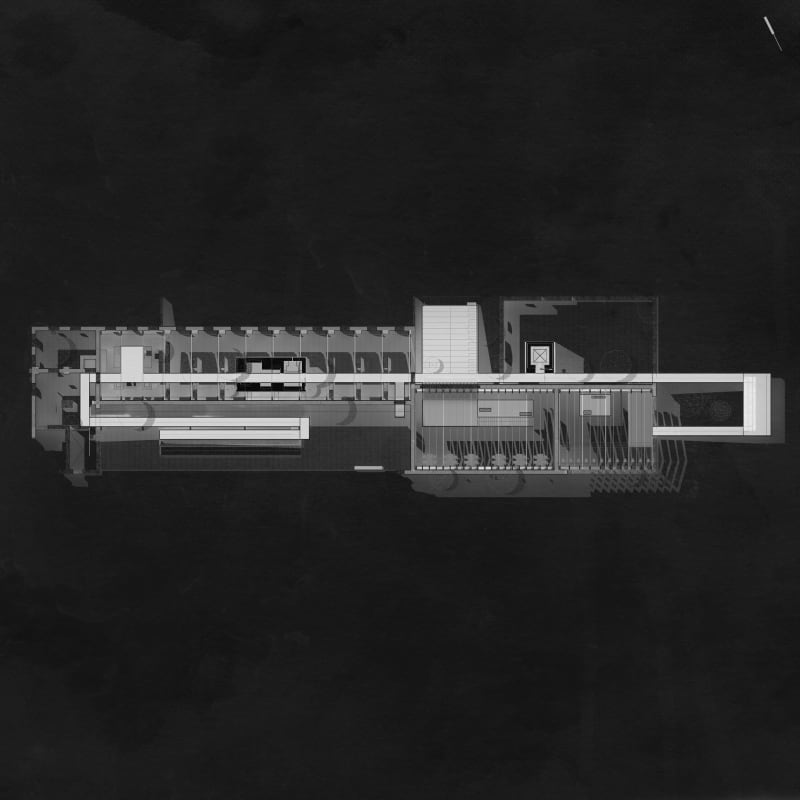

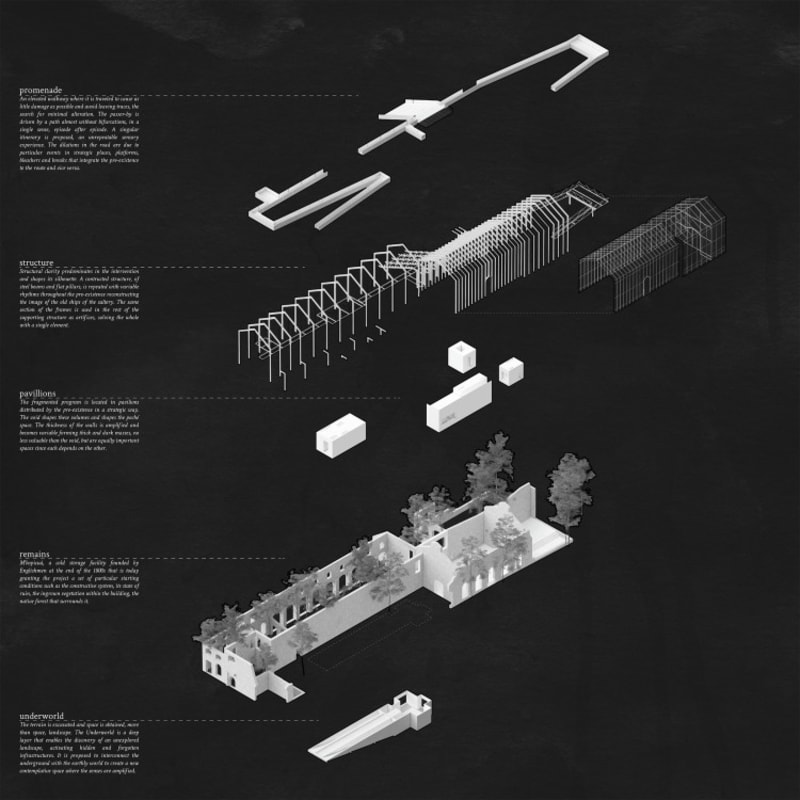

We finally divided our intervention in 5 components:

First, the remains are the base;

Below, the underworld, a dig landscape that integrates a web of existing tunnels to the visitor experience;

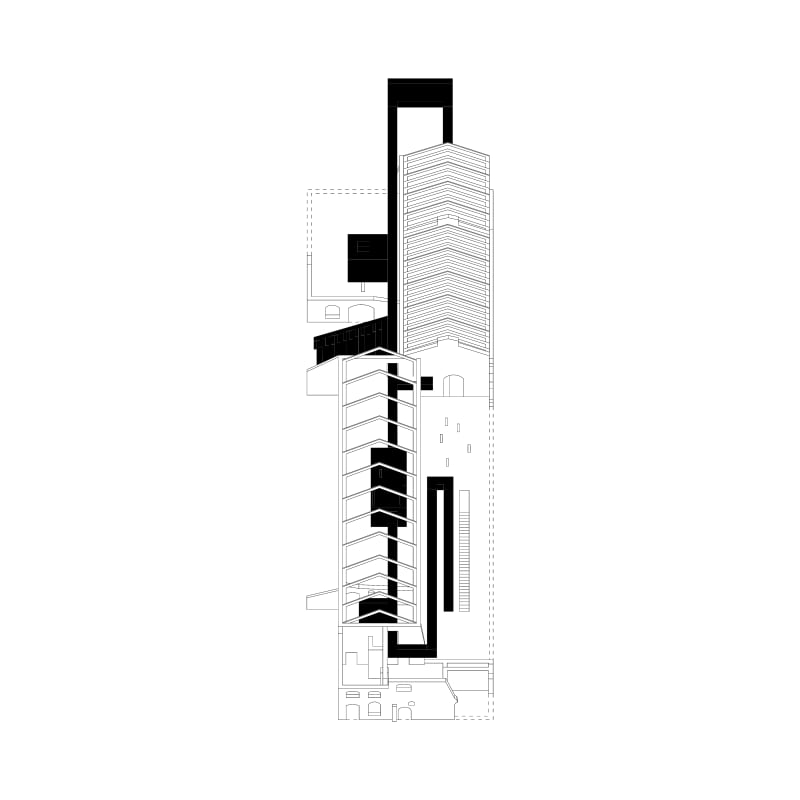

Then the structure, a series of portal frames that define the anatomy of the composition;

After that, the promenade, a one-way path with some bifurcations that allow us to walk the existent in an alternative way;

And the pavillions, a fragmented program that boosts the interaction between the user with the environment that he observes.

The Interpretation Center M’Bopicuá is positioned inside and outside the preexistence, adding a new level of comprehension of the site, coexististing with the construction and the native forest.