& other waters is a response to the static view of architectures in places of constant change; by releasing architecture from its static formalism, allows for transformative, flexible re-inventions of place that mediates between the ephemeral and the permanent. The project investigates the cyclic nature of Óbuda Island, Budapest, presenting a project in the midst of change, development, destruction and re-appropriation.

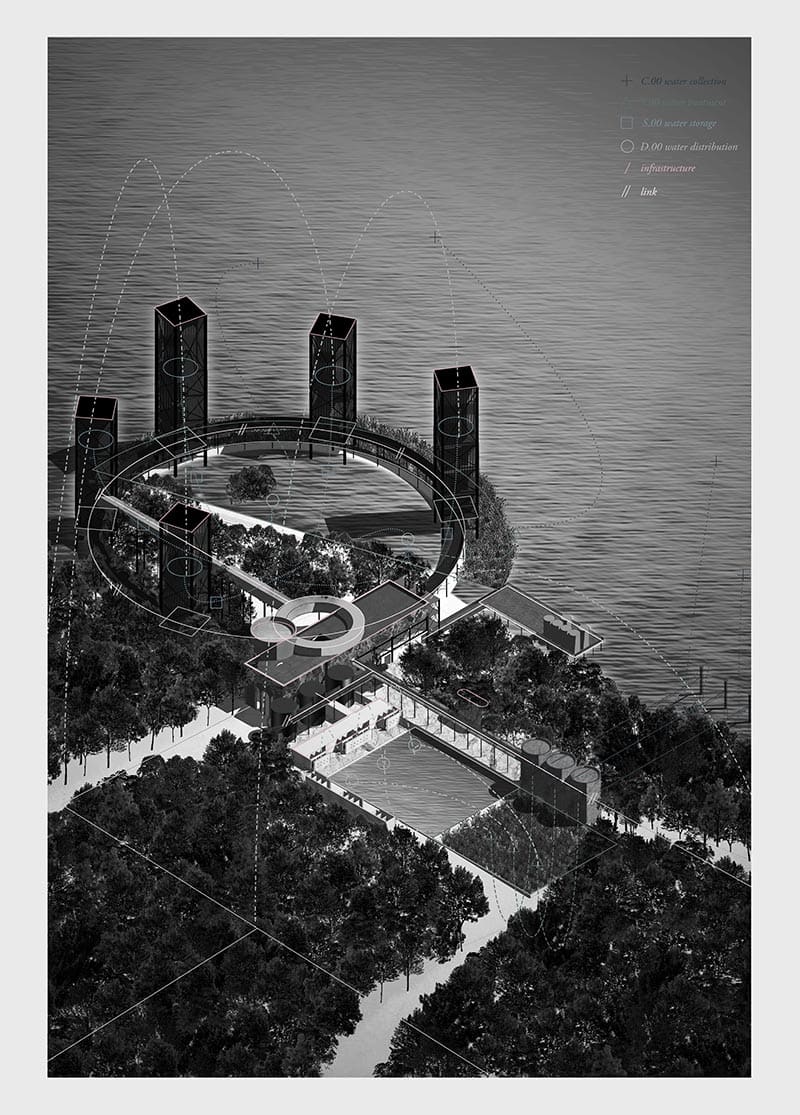

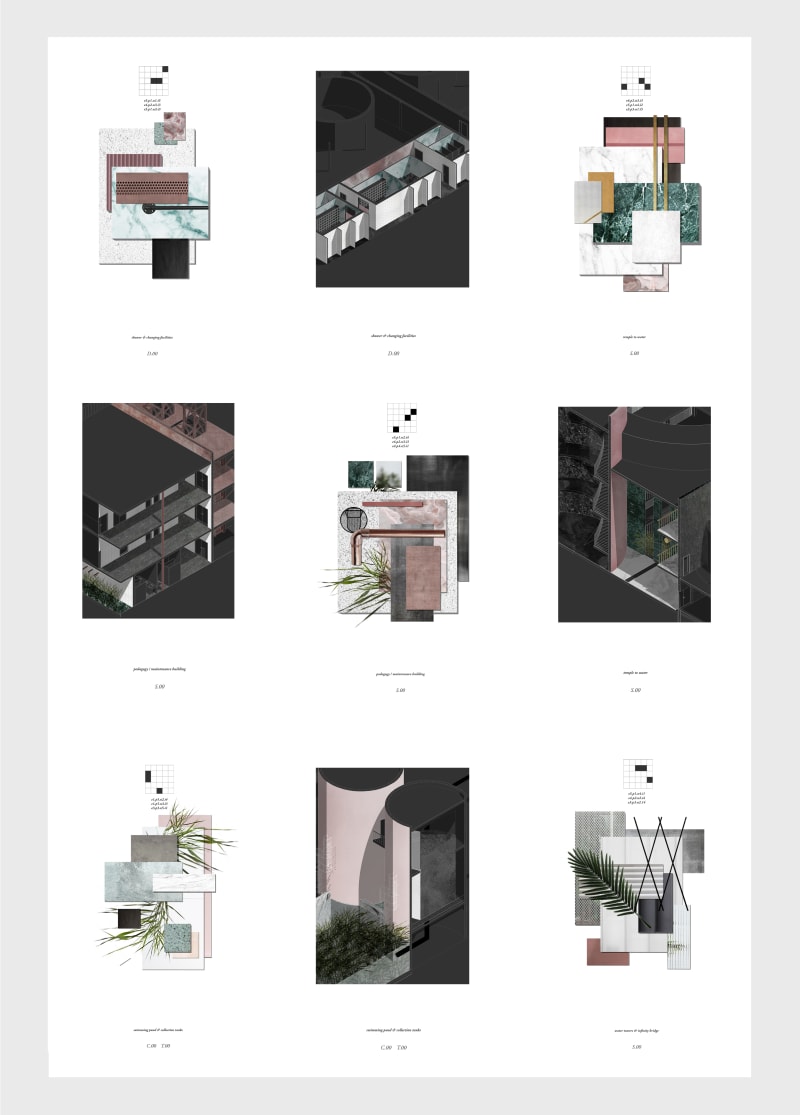

The project seeks to challenge the potentials for providing infrastructures of necessity and utility {water}, and cross-breeding it with temporal social programmes; that in turn provide positive environmental side effects. These infrastructures present a framework with open-space and dynamic platforms that are capable of hosting varying and ever-changing contents in response to the islands needs.

& other waters is a metaphor of architecture that demands for a better spatial understanding of the space and place in which society live, work and play. Through the spatial understanding, ‘architecture’ – as a term – expands to open up its possibilities to be understood much more than a ‘static’ object, and in turn, radically broadens it’s ability to respond to a temporal society.

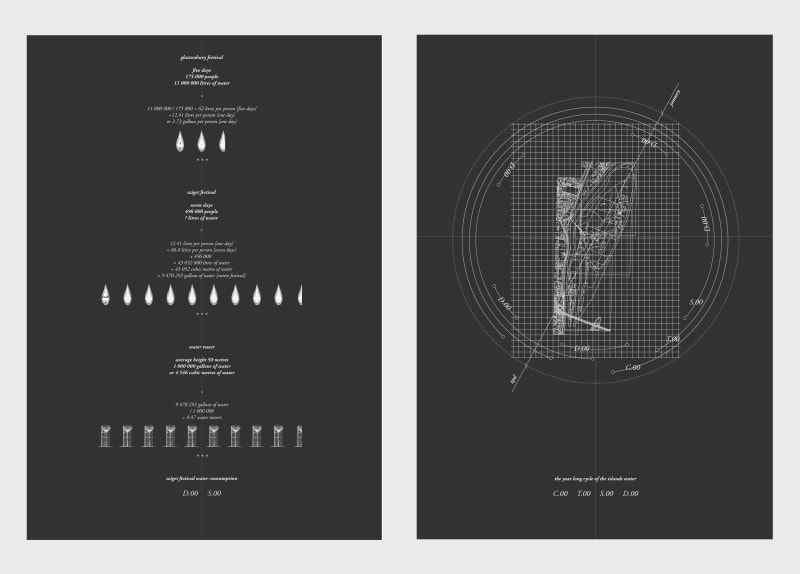

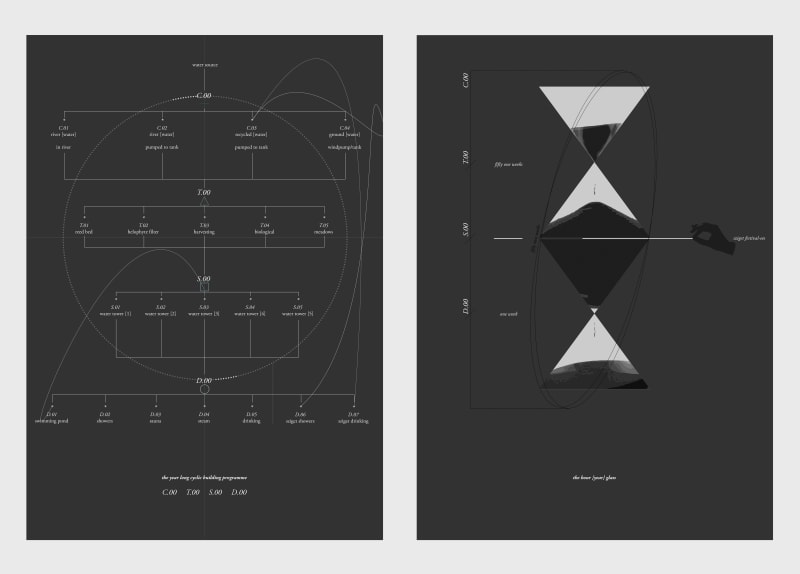

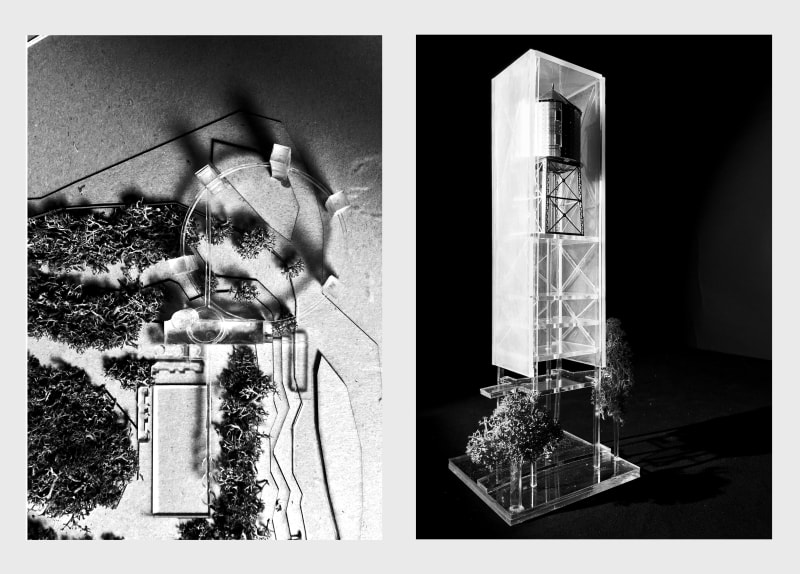

The project presents – in short – a biological water treatment facility which allows for river water to be sustainably collected, treated and stored throughout the year that eventually provides clean water to 500,000 festival-ees. Presenting a cyclic programme which is a reaction to Óbuda Islands life cycle and a response to a site which is ultimately temporal.

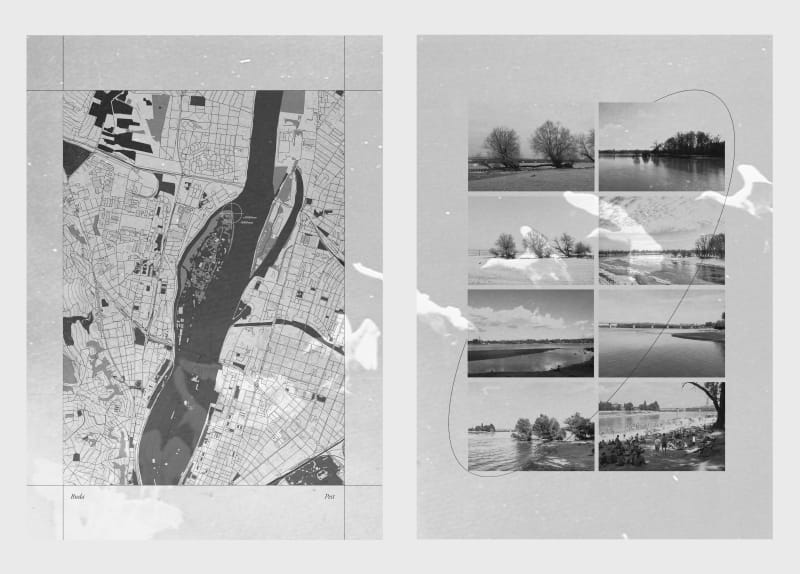

The site’s temporality and its flux can be seen through it’s history, island programme, and it’s re-emerging and submerging landscape. The island is understood to be ‘in flight’ throughout its fifty-two week year-glass. & other waters echoes this cyclic nature of the island and in turn evokes a project that too moves with it’s context through constant re-inventions of the architectures.

The year-glass theory of the island represents it’s programmatic nature; for fifty-one weeks of the year presents an island in flux, until it is turned upside down when 500,000 people visit its annual festival; Sziget. The programme responds to the narrative through an investigation in water consumption of such an event and in turn aims to re-imagine how architecture can present a response to this. The sustainable and natural water treatment facility takes the utility of water, and gives the infrastructures possibility and poetry through cross-breeding programmes in response to its cyclic nature.

For the year-glass to be successful, it must respond to the natural qualities of the island. Throughout its fifty-one weeks of the year the water slowly trickles through the systems, and in turn responds to the island’s time by creating regenerative designs that can be constantly re-invented throughout the fifty-one weeks; through such systems, the site becomes a place in time.

The biological water-treatment facility introduces a vast reed-bed system, and rather than simply treating the water, the system extends beyond this by cross-breeding programmes to provide social benefits; the treatment facilities become leisure facilities through their use of swimming bonds, and by cross-breeding the industrial with the natural, the permanent and the ephemeral, the facility curates on the site, a networks of different programmes.

The spaces have been designed so that it allows for variations of programmes within the infrastructure system as a reference to permit present and future configurations of space to be arranged and assembled when the need is changed throughout the year. The proposal echoes the flight of the island through the fluctuating programmatic needs of the site throughout it’s yearly cycle.

Materials assigned to the architectures to react to the environment through their degrees of intervention of the site, as well as reflecting the qualities of the uses within the islands re-interpreted year-glass. Materiality is key to embodying the temporalities within the site and thus their ever-changing programmes. Through a methodological process, the curation of a material matrix allows for the material to be systematically assigned based on their permanence to reflect the function through the details.

The infrastructures of the project mediate between the ephemeral and the permanent, a simulacrum to address the nature of the typographic structure of the water tower; an industrial architecture that has begun to disappear within society. Though there is variation to the specificity of the form of a tower, and within the new typologies, allow for potential within the naked forms that lye below it’s tank. A new typology of the water tower is formed and presents new characteristics and adaptability. The towers present a project in the midst of change, development, destruction and re-appropriation. Modified by what happens inside and out, they will continue to be renovated and transformed depending on the needs of an island continuously in flight.

The purpose of & other waters is to investigate the possibilities for architecture to embody the continuity of time in design. Temporality in architecture is often neglected as design tends to take a stance for permanence and durability. This overlooking of the temporal often means that architecture is not understood in the context of the fluidity of time. Time, as we know it, is not fixed – instead it is an organic entity that is endlessly evolved to be constantly reinvented, and with this understanding, space and place have the ability to become a fountain-head of experiential ways of conceiving space of constant re-invention.

Cedric Price proposed the idea of a time-based approach to architecture “conceived as a series of interventions that were both adaptable and impermanent.” Acknowledging that architecture is often too slow in solving immediate problems; and thus opposed the development of buildings that were limited for a particular function. Instead he stressed that buildings needed to be constructed for adaptability because of the unpredictability of the future use of spaces.

This project calls for an understanding which mediates between the ephemeral and the permanent, in creating flexible and dynamic architectures that respond to the everyday – the reality of a world where change is constant and even increasing in speed is that nothing lasts.

Óbuda